Way of St. James

| Route of Santiago de Compostela* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|

|

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 669 |

| Region** | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1993 (17th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. |

|

The Way of St. James or St. James' Way (Spanish: El Camino de Santiago, Galician: O Camiño de Santiago, French: Chemin de St-Jacques, German: Jakobsweg) is the pilgrimage to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia in northwestern Spain, where tradition has it that the remains of the apostle Saint James are buried.

Contents |

Major Christian pilgrimage route

The Way of St James has existed for over a thousand years. It was one of the most important Christian pilgrimages during medieval times, together with Rome and Jerusalem, and a pilgrimage route on which a plenary indulgence could be earned;[1] other major pilgrimage routes include the Via Francigena to Rome and the pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

Legend holds that St. James's remains were carried by boat from Jerusalem to northern Spain where he was buried on the site of what is now the city of Santiago de Compostela. There are some, however, who claim that the bodily remains at Santiago belong to Priscillian, the fourth-century Galician leader of an ascetic Christian sect, Priscillianism, who was one of the first Christians to be executed .

The Way can take one of any number of pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela. Traditionally, as with most pilgrimages, the Way of Saint James began at one's home and ended at the pilgrimage site. However a few of the routes are considered main ones. During the Middle Ages, the route was highly traveled. However, the Black Plague, the Protestant Reformation and political unrest in 16th-century Europe led to its decline. By the 1980s, only a few pilgrims arrived in Santiago annually. Since then however the route has attracted a growing number of modern-day pilgrims from around the globe. The route was declared the first European Cultural Route by the Council of Europe in October 1987; it was also named one of UNESCO's World Heritage Sites.

Whenever St James's day (25 July) falls on a Sunday, the cathedral declares a Holy or Jubilee Year. Depending on leap years, Holy Years occur in 5, 6 and 11 year intervals. The most recent were 1982, 1993, 1999, 2004, and 2010. The next will be 2021, 2027, and 2032.

History

The pilgrimage to Santiago has never ceased from the time of the discovery of St. James' remains, though there have been years of fewer pilgrims, particularly during European wars. During the war of American Independence, John Adams was ordered by Congress to go to Paris to obtain funds for the cause. His ship started leaking and he disembarked with his two sons in Finisterre in 1779, where he proceeded to follow the Way of St. James in the opposite direction, in order to get to Paris overland. He did not stop to visit Santiago, and came to regret this during the course of his journey. In his autobiography, he gives an accurate description of the customs and lodgings afforded to St. James pilgrims in the 18th century, and mentions the legend as it was then told to travellers:

| “ | I have always regretted that We could not find time to make a Pilgrimage to Saint Iago de Compostella. We were informed, ... that the Original of this Shrine and Temple of St. Iago was this. A certain Shepherd saw a bright Light there in the night. Afterwards it was revealed to an Archbishop that St. James was buried there. This laid the Foundation of a Church, and they have built an Altar on the Spot where the Shepherd saw the Light. In the time of the Moors, the People made a Vow, that if the Moors should be driven from this Country, they would give a certain portion of the Income of their Lands to Saint James. The Moors were defeated and expelled and it was reported and believed, that Saint James was in the Battle and fought with a drawn Sword at the head of the Spanish Troops, on Horseback. The People, believing that they owed the Victory to the Saint, very cheerfully fulfilled their Vows by paying the Tribute. ...Upon the Supposition that this is the place of the Sepulchre of Saint James, there are great numbers of Pilgrims, who visit it, every Year, from France, Spain, Italy and other parts of Europe, many of them on foot. | ” |

|

—Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society, [2] |

||

Pre-Christian history

The route to Santiago de Compostela was a Roman trade route, nicknamed the Milky Way by travellers, as it followed the Milky Way to the Atlantic Ocean.[3]

The Christian origin of the pilgrimage has been well documented throughout the centuries, but no historical reference has ever been found for the pagan origins.

The scallop, which resembles the setting sun, may have been a symbol used in pre-Christian Celtic rituals of the area. It may be that the Way of St. James may have originated as a pre-Christian Celtic death journey westwards towards the setting sun,[4] terminating at the "End of the World" (Finisterra) on the "Coast of Death" (Costa da Morte)[4] and the "Sea of Darkness" (that is, the Abyss of Death, the Mare Tenebrosum, Latin for the Atlantic Ocean, itself named after the Dying Civilization of Atlantis), but no evidence has ever been found.

To this day, many pilgrims continue from Santiago de Compostela to the Atlantic coast of Galicia, to finish their journeys at Spain's westernmost point, Cape Finisterre. Although Cape Finisterre is not the westernmost point of mainland Europe (Cabo da Roca in Portugal is further west), the fact that the Romans called it Finisterrae (literally the end of the world or Land's End in Latin) indicates that they viewed it as such.

The Pilgrims' road seems related to prehistoric cults of fertility arriving to Atlantic Europe from Mediterranean shores. Symbols that may be of Ashtarte, the star within a circle, or Aphrodite, Venus coming on a shell, have been found along the roads to Compostela and among the ancient Basques' mythology and legends, those related to Mari, the Mairu and the rising of Megaliths. Joseph Campbell associated the cult of Mari to that of Ishtar and Kali and in pre-Israelites times, the rejected consort of God called "the great prostitute", Asherah.

Scallop symbol

The scallop shell, typically found on the shores in Galicia, has long been the symbol of the Camino de Santiago. Over the centuries the scallop shell has taken on mythical, metaphorical and practical meaning, even if its relevance is actually due to pilgrims wishing to take a souvenir back to their places of origin.

There are different accounts of the mythical origin of the symbol. Which account is taken depends on who is telling the story. Two versions of the most common myth are:

James the Greater, the brother of John, was killed in Jerusalem for his convictions about his brother. James had spent some time preaching on the Iberian Peninsula.

- (version 1) After James' death, his disciples shipped his body to the Iberian Peninsula to be buried in what is now Santiago. Off the coast of Spain a heavy storm hit the ship, and the body was lost to the ocean. After some time, however, the body washed ashore undamaged, covered in scallops.

- (version 2) After James' death his body was mysteriously transported by a ship with no crew back to the Iberian Peninsula to be buried in what is now Santiago. As James' ship approached land, a wedding was taking place on the shore. The young bridegroom was on horseback, and on seeing the ship approaching, his horse got spooked, and the horse and rider plunged into the sea. Through miraculous intervention, the horse and rider emerged from the water alive, covered in seashells.

Besides being the mythical symbol, the scallop shell also acts as a metaphor. The grooves in the shell, which come together at a single point, represent the various routes pilgrims traveled, eventually arriving at a single destination: the tomb of Saint James in Santiago de Compostela. The scallop shell is also a metaphor for the pilgrim. As the waves of the ocean wash scallop shells up on the shores of Galicia, God's hand also guided the pilgrims to Santiago.

The scallop shell served practical purposes for pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago as well. The shell was the right size for gathering water to drink or for eating out of as a makeshift bowl. Also, because the scallop shell is native to the shores of Galicia, the shell functioned as proof of completion. By having a scallop shell, a pilgrim could almost certainly prove that he or she had finished the pilgrimage and had actually seen the "end of the world" which at that point in history was the Western coast of Spain.

The reference to St. James rescuing a "knight covered in scallops" is therefore a reference to St. James healing, or resurrecting, a dying (setting sun) knight. Note also that the knight obviously would have had to be "under the waters of death" for quite some time for shellfish to have grown over him. Similarly, the notion of the "Sea of Darkness" (Atlantic Ocean) disgorging St. James' body, so that his relics are (allegedly) buried at Santiago de Compostela on the coast, is itself a metaphor for "rising up out of Death", that is, resurrection.

The pilgrim's staff is a walking stick used by pilgrims to the shrine of Santiago de Compostela in Spain.[5] Generally, the stick has a hook on it so that something may be hung from it. The walking stick sometimes has a cross piece on it.[6]

Medieval route

The earliest records of visits paid to the shrine dedicated to St. James at Santiago de Compostela date from the 8th century, in the time of the Kingdom of Asturias. The pilgrimage to the shrine became the most renowned medieval pilgrimage, and it became customary for those who returned from Compostela to carry back with them a Galician scallop shell as proof of their completion of the journey. This practice was gradually extended to other pilgrimages.

The earliest recorded pilgrims from beyond the Pyrenees visited the shrine in the middle of the 10th century, but it seems that it was not until a century later that large numbers of pilgrims from abroad were regularly journeying there. The earliest records of pilgrims that arrived from England belong to the period between 1092 and 1105. However, by the early 12th century the pilgrimage had become a highly organized affair.

One of the great proponents of the pilgrimage in the 12th century was Calixtus II who started the Compostelan Holy Years.[7] The official guide in those times was the Codex Calixtinus. Published around 1140, the 5th book of the Codex is still considered the definitive source for many modern guidebooks. Four pilgrimage routes listed in the Codex originate in France and converge at Puente la Reina. From there, a well-defined route crosses northern Spain, linking Burgos, Carrión de los Condes, Sahagún, León, Astorga, and Compostela.

The daily needs of pilgrims on their way to and from Compostela were met by a series of hospitals and hospices. These had royal protection and were a lucrative source of revenue. Romanesque architecture, a new genre of ecclesiastical architecture, was designed with massive archways to cope with huge devout crowds. There was also the sale of the now-familiar paraphernalia of tourism, such as badges and souvenirs. Since the Christian symbol for James the Greater was the scallop shell, many pilgrims wore one as a sign to anyone on the road that they were a pilgrim. This gave them privileges to sleep in churches and ask for free meals, but also warded off thieves who dared not attack devoted pilgrims.

The pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela was possible because of the protection and freedom provided by the Kingdom of France, where the majority of pilgrims originated. Enterprising French people (including Gascons and other peoples not under the French crown) settled in towns along the pilgrimage routes, where their names appear in the archives. The pilgrims were tended by people like Domingo de la Calzada who was later recognized as a saint himself.

Pilgrims walked the Way of St. James, often for months, to arrive at the great church in the main square of Compostela and pay homage to St. James. So many pilgrims have laid their hands on the pillar just inside the doorway of the church that a groove has been worn in the stone.

The popular Spanish name for the astronomical Milky Way is El Camino de Santiago. According to a common medieval legend, the Milky Way was formed from the dust raised by travelling pilgrims.[8] Compostela itself means "field of stars". Another origin for this popular name is Book IV of the Book of Saint James which relates how the saint appeared in a dream to Charlemagne, urging him to liberate his tomb from the Moors and showing him the direction to follow by the route of the Milky Way.

As penance

The Church employed a system of rituals to atone for temporal punishment due to sins known as penance. According to this system, pilgrimages were a suitable form of expiation for some temporal punishment, and they could be used as acts of penance for those who were guilty of certain crimes. As noted in the Catholic Encyclopedia,

| “ |

|

” |

There is still a tradition in Flanders of freeing one prisoner a year[10] under the condition that this prisoner walk to Santiago wearing a heavy backpack, accompanied by a guard.

The modern-day pilgrimage

Today tens of thousands[11] of Christian pilgrims and other travellers set out each year from their front doorstep, or popular starting points across Europe, to make their way to Santiago de Compostela. Most travel by foot, some by bicycle, and a few travel as some of their medieval counterparts did, on horseback or by donkey (for example, the British author and humorist Tim Moore). In addition to people undertaking a religious pilgrimage, there are many travellers and hikers who walk the route for non-religious reasons: travel, sport, or simply the challenge of weeks of walking in a foreign land. Also, many consider the experience a spiritual adventure to remove themselves from the bustle of modern life. It acts as a retreat for many modern "pilgrims".

Routes

Pilgrims on the Way of St. James walk for weeks or months to visit the city of Santiago de Compostela. They follow many routes (any path to Santiago is a pilgrim's path) but the most popular route is Via Regia and its last part - the French Way (Camino Francés). Historically, most of the pilgrims came from France, from Paris, Vézelay, Le Puy and Arles and Saint Gilles, due to the Codex Calixtinus. These are today important starting points. The Spanish consider the Pyrenees a starting point. Common starting points along the French border are Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port or Somport on the French side of the Pyrenees and Roncesvalles or Jaca on the Spanish side. (The distance from Roncesvalles to Santiago de Compostella through León is about 800 km.). Another possibility is to do the Northern Route that was first used by the pilgrims in order to avoid travelling through the territories occupied by the Muslims in the Middle Ages. The greatest attraction is its landscape, as a large part of the route runs along the coastline against a backdrop of mountains and overlooking the Cantabrian Sea.

However, many pilgrims begin further afield, in one of the four French towns which are common and traditional starting points: Paris, Vézelay, Arles and Le Puy. Cluny, site of the celebrated medieval abbey, was another important rallying point for pilgrims and, in 2002, it was integrated into the official European pilgrimage route linking Vézelay and Le Puy. Some pilgrims start from even further away, though their routes will often pass through one of the four French towns mentioned. Some Europeans begin their pilgrimage from the very doorstep of their homes just as their medieval counterparts did hundreds of years ago.

Another popular route is the 227 km long Portuguese Way, which starts at Se Catedral in the city of Porto in the north of Portugal. One of most tiring parts of the Portuguese Way is in Labruja parish in Ponte de Lima, because it is through the Labruja hills, which are hard to cross. The camino winds its way inland until it reaches the Spanish border. Many pilgrims prefer to start closer to the Spanish border at Valença, Portugal, and Tui, Galicia, for a five-day, 108 km walk.

Accommodation

In Spain and France, pilgrim's hostels with beds in dormitories dot the common routes, providing overnight accommodation for pilgrims who hold a credencial (see below). In Spain this type of accommodation is called a refugio or albergue, both of which are similar to youth hostels or hostelries in the French system of gîtes d'étape. They usually cost between three and seven euros per night, but a few operate on voluntary donations and are known as donativos. Pilgrims are usually limited to one night's accommodation.

These hostels may be run by the local parish, the local council, private owners, or pilgrims' associations. Occasionally these refugios are located in monasteries, such as the one in Samos, Spain, run by monks or the one in Santiago de Compostela.

Credencial or pilgrim's passport

Most pilgrims have a document called the credencial, which they have purchased for a few euros through a Spanish tourist agency or their local church, depending on their starting location. The credencial is a pass which allows (sometimes free) overnight accommodation in refugios. Also known as the "pilgrim's passport", the credencial is stamped with the official St. James stamp of each town or refugio at which the pilgrim has stayed. It provides walking pilgrims with a record of where they ate or slept, but also serves as proof to the Pilgrim's Office in Santiago that the journey is accomplished according to an official route. The credencial is available at refugios, tourist offices, some local parish houses, and outside Spain, through the national St. James organisation of that country. The stamped credencial is also necessary if the pilgrim wants to obtain a compostela, a certificate of completion of the pilgrimage.

Most often the stamp can be obtained in the refugio, cathedral or local church. If the church is closed, the town hall or office of tourism can provide a stamp, as well as nearby youth hostels or private St. James addresses. Outside Spain, the stamp can be associated with something of a ceremony, where the stamper and the pilgrim can share information. As the pilgrimage approaches Santiago, many of the stamps in small towns are self-service due to the greater number of pilgrims, while in the larger towns there are several options to obtain the stamp.

Compostela

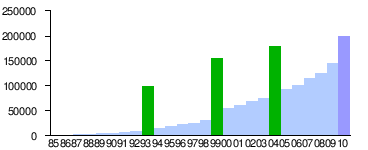

Green bars are holy years |

The compostela is a certificate of accomplishment given to pilgrims on completing the Way. To earn the compostela one needs to walk a minimum of 100 km or cycle at least 200 km. In practice, for walkers, that means starting in the small city of Sarria, for it has good transportation connections via bus and rail to other places in Spain. Pilgrims arriving in Santiago de Compostela who have walked at least the last 100 km, or cycled 200 km to get there (as indicated on their credencial), are eligible for the compostela from the Pilgrim's Office in Santiago.

The compostela has been indulgenced since the Early Middle Ages and remains so to this day.[12] The full text of the certificate is in Latin and reads:

CAPITULUM hujus Almae Apostolicae et Metropolitanae Ecclesiae Compostellanae sigilli Altaris Beati Jacobi Apostoli custos, ut omnibus Fidelibus et Perigrinis ex toto terrarum Orbe, devotionis affectu vel voti causa, ad limina Apostoli Nostri Hispaniarum Patroni ac Tutelaris SANCTI JACOBI convenientibus, authenticas visitationis litteras expediat, omnibus et singulis praesentes inspecturis, notum facit : (Latin version of name of recipient) Hoc sacratissimum Templum pietatis causa devote visitasse. In quorum fidem praesentes litteras, sigillo ejusdem Sanctae Ecclesiae munitas, ei confero. Datum Compostellae die (day) mensis (month) anno Dni (year) Canonicus Deputatus pro Peregrinis

The pilgrim passport is examined carefully for stamps and dates. If a key stamp is missing, or if the pilgrim does not claim a religious purpose for their pilgrimage, the compostela may be refused. The Pilgrim Office of Santiago awards more than 100,000 compostelas a year to pilgrims from over 100 countries.

Pilgrim's Mass

A Pilgrim's Mass is held in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela each day at noon for pilgrims. Pilgrims who received the compostela the day before have their countries of origin and the starting point of their pilgrimage announced at the Mass. The musical and visual highlight of the mass is the synchronisation of the beautiful "Hymn to Christ" with the spectacular swinging of the huge Botafumeiro, the famous thurible kept in the cathedral. Incense is burned in this swinging metal container, or "incensory". As the last chords die away, the multitude of pilgrims jostle happily as they crowd forward to reach the spiritual highlight of the Mass, the rite of communion. Priests administer the Sacrament of Penance, or confession, in many languages, permitting most pilgrims to complete the indulgence attached to the pilgrimage upon satisfying the other canonical conditions.

As tourism

| Year | Pilgrims |

|---|---|

| 1985 | 690 |

| 1986 | 1,801 |

| 1987 | 2,905 |

| 1988 | 3,501 |

| 1989 | 5,760² |

| 1990 | 4,918 |

| 1991 | 7,274 |

| 1992 | 9,764 |

| 1993 | 99,4361 |

| 1994 | 15,863 |

| 1995 | 19,821 |

| 1996 | 23,218 |

| 1997 | 25,179 |

| 1998 | 30,126 |

| 1999 | 154,6131 |

| 2000 | 55,004³ |

| 2001 | 61,418 |

| 2002 | 68,952 |

| 2003 | 74,614 |

| 2004 | 179,9441 |

| 2005 | 93,924 |

| 2006 | 100,377 |

| 2007 | 114,026 |

| 2008 | 125,141 |

| 2009 | 145,877 |

| 2010 | >200,0001 (est.) |

| 1 Holy Years (Xacobeo/Jacobeo) 2 4th World Youth Day in Santiago de Compostela |

|

The Xunta de Galicia (Galicia's regional government) promotes the Way as a tourist activity, particularly in Holy Compostellan Years (when July 25 falls on a Sunday). Following the Xunta's considerable investment and hugely successful advertising campaign for the Holy Year of 1993, the number of pilgrims completing the route has been steadily rising. Following the Holy Year of 2010, the next Holy Year will not be for another 11 years, and over 200,000 pilgrims are expected to make the trip during the course of 2010.[15]

Below is a table detailing the numbers of pilgrims recorded as arriving at the cathedral at Santiago each year from 1985. The figures are sourced from the cathedral's records.

In television and film

The Way of St James was the central feature of the film Saint Jacques... La Mecque directed by Coline Serreau in 2005.

Art critic and journalist Brian Sewell made a journey to Santiago de Compostela for a television series The Naked Pilgrim for UK's Channel Five in 2003. Travelling by car along the French route, he visited many towns and cities on the way including Paris, Chartres, Roncesvalles, Burgos, Leon and Frómista. Sewell, a lapsed Catholic, was moved by the stories of other pilgrims and by the sights he saw. The series climaxed with Sewell's emotional response to the Mass at Compostela.

The pilgrimage is central to the plot of the 1969 film The Milky Way by surrealist director Luis Buñuel. However, the film is intended to be a critique of the Catholic church, as the modern pilgrims encounter various manifestations of Catholic dogma and heresy.

Emilio Estevez has written, directed and starred in the film "The Way" starring Martin Sheen, his father. The film will be presented at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2010.[16][17]

Name in other languages

The Way of St. James is most often referred to by the names used in the areas it passes:

- Galician: O Camiño de Santiago or Ruta Xacobea

- Spanish: El Camino de Santiago or simply El Camino

- Basque: Donejakue Bidea

- French: Le Chemin de Saint Jacques

- Portuguese: O Caminho de Santiago

See also

- World Heritage Sites of the Routes of Santiago de Compostela in France

- Confraternity of Saint James

- Order of Santiago

- Dominic de la Calzada

- Cross of Saint James

- ViaJacobi

References

- ↑

Kent, William H. (1913). "Indulgences". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.. This entry on indulgences suggests that the evolution of the doctrine came to include pilgrimage to shrines as a trend that developed from the eighth century A.D.:

Kent, William H. (1913). "Indulgences". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.. This entry on indulgences suggests that the evolution of the doctrine came to include pilgrimage to shrines as a trend that developed from the eighth century A.D.:

“ Among other forms of commutation were pilgrimages to well-known shrines such as that at St. Albans in England or at Compostela in Spain. But the most important place of pilgrimage was Rome. According to Bede (674-735) the "visitatio liminum", or visit to the tomb of the Apostles, was even then regarded as a good work of great efficacy (Hist. Eccl., IV, 23). At first the pilgrims came simply to venerate the relics of the Apostles and martyrs; but in course of time their chief purpose was to gain the indulgences granted by the pope and attached especially to the Stations. ” - ↑ "John Adams autobiography, part 3, Peace, 1779-1780, sheet 10 of 18". Harvard University Press, 1961. August 2007. http://www.masshist.org/digitaladams.

- ↑ "Medieval footpath under the stars of the milky way". Telegraph Online.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Thomas, Isabella. "Pilgrim's Progress". Europe in the UK. European Commission.

- ↑ Pilgrim's or Palmer's Staff (fr. bourdon): this was used as a device in a coat of arms as early at least as Edward II's reign, as will be seen. The Staff and the Escallop shell (q.v.) were the badge of the pilgrim, and hence it is but natural it should find its way into the shields of those who had visited the Holy Land. The usual form of representation is figure 1, but in some the hook is wanting, and when this is the case it is scarcely distinguishable from a pastoral staff as borne by some of the monasteries: it is shown in figure 2. While, too, it is represented under different forms, it is blazoned as will be seen also, under different names, e.g. a pilgrim's crutch, a crutch-staff, &c., but there is no reason to suppose that the different names can be correlated with different figures. The crutch, perhaps, should be represented with the transverse piece on the top of the staff (like the letter T) instead of across it. heraldsnet.org

- ↑ "Brief history: The Camino – past, present & future". Camino Pilgrim Guides.

- ↑ Bignami, Giovanni F. (26 March 2004). "Visions of the Milky Way". Science 303 (5666): 1979.

- ↑ "Pilgrimages". New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia, retrieved Dec 1, 2006.

- ↑ "Huellas españolas en Flandes". Turismo de Bélgica.

- ↑ "The present-day pilgrimage". The Confraternity of Saint James. http://www.csj.org.uk/present.htm.

- ↑ "The Compostela and the plenary indulgence". The Confraternity of Saint James.

- ↑ Pilgrims by year according to the office of pilgrims at the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela

- ↑ Pilgrims 2006-2009 according to the office of pilgrims at the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela

- ↑ "Spain: 200,000 pilgrims expected for the 'Year of St. James 2010'". Documentation Information Catholiques Internationales. 1 October 2009.

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1441912/

- ↑ The way official movie site

Further reading

Pilgrim's guides and travelogues

- Confraternity of St. James, "Pilgrim Guides To Spain 1. The Camino Francés".

- Kathryn Harrison, "The Road to Santiago", National Geographic Directions, 2003 .

- Film documenting one man's spiritual journey along the Camino

Fiction and other literary works

- Paulo Coelho, The Pilgrimage (1987)

- James Michener, Iberia (1968); contains one chapter about the Camino de Santiago

- Walter Starkie, The Road to Santiago, (1957) John Murray, reprinted 2003.

- David Lodge, Therapy (1995)

- Anne Carson - "Kinds of Water" first published in 1987. A prose poem that traces the narrator's journey, focusing on the philosophical questions it raises, especially with regards to the nature and desire of the pilgrim. The piece can be found in the 1995 anthology of Carson's essays Plainwater.

External links

General information

- El Camino de Santiago | The pilgrimage route to Compostela. - Maps, stages, planning, how to get there, accommodation, photos etc.

- The Northern Way of St. James (El Camino del Norte) Map and photos.

- Santiago de Compostela Cathedral - Official site

Camino confraternities

- The Confraternity of Saint James, England

- American Pilgrims on the Camino

- Canadian Company of Pilgrims

Travel information

- Pilgrim Wiki, a pilgrim guide written by pilgrims

- The Camino - The pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela in pictures

- General information about the Camino de Santiago de Compostela

- Guide to walking the Camino de Santiago de Compostela

- Way of St. James travel guide from Wikitravel

Link collections

- Xacowebs Collection of websites related to Way of St. James

- International Bibliography

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||